There is a pretty good chance that you are not smart enough to do this book review justice, or at least not wise enough. This is more your wife's territory. Liz has both the wisdom and the spiritual intelligence to explore all of the richness this story deserves. You probably do not. Nevertheless, (and since she refused to write this review for you) here goes nothing.

"Life of Pi" is about a boy named Pi, but it is not the story of his life. It is only the story of his experience as a young boy growing up in a charming seaside town in India in a family that owned a zoo. But, more importantly, it is a story about his extraordinary transformation into an adult. At the age of sixteen, Pi survives a shipwreck and lives on a lifeboat in the Pacific for an incredible amount of time. He floats on the open ocean until he lands on a Mexican beach where the story promptly ends.

But that's not what the book is about.

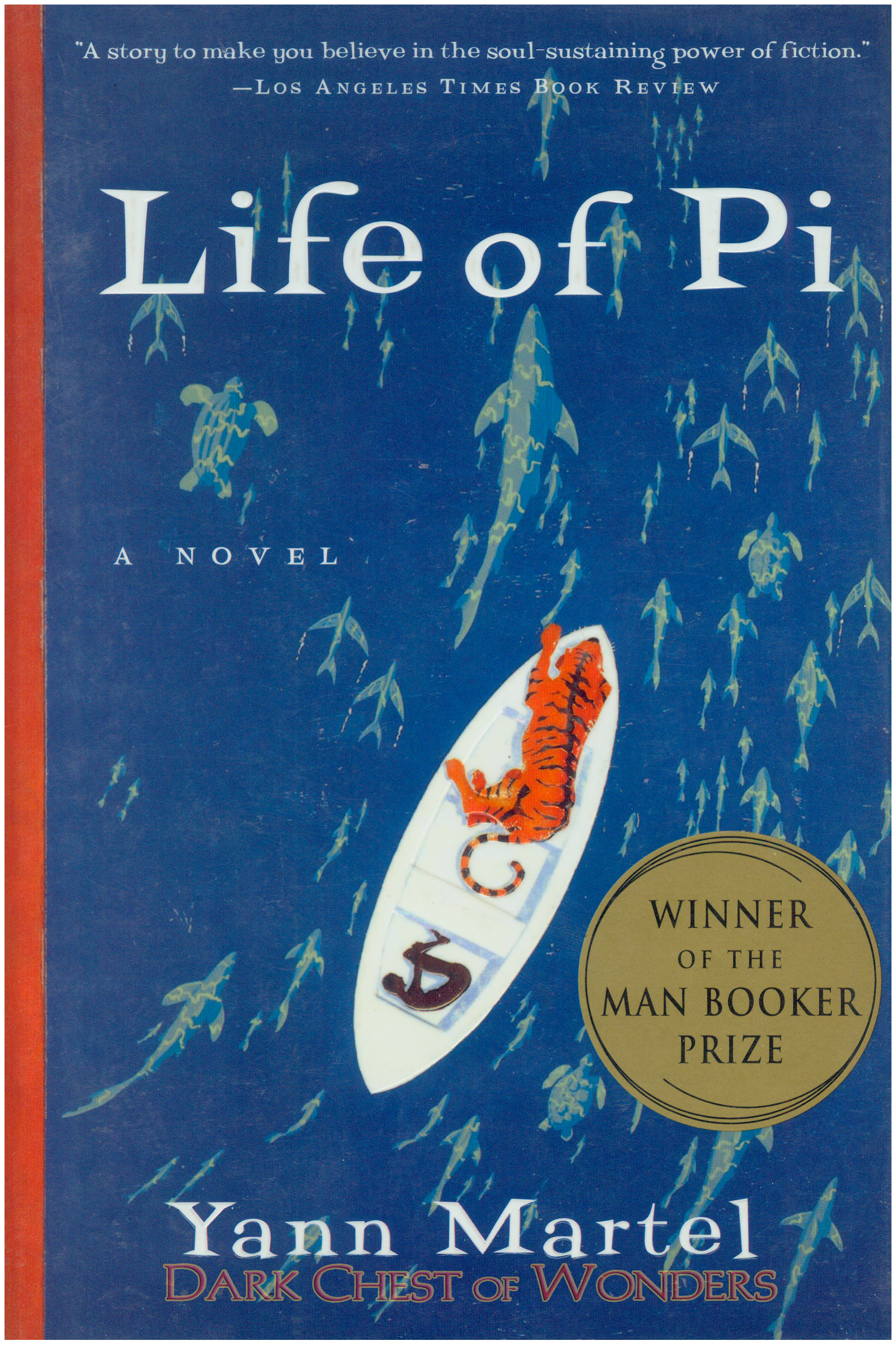

There is a tiger, named Richard Parker, on the lifeboat with Pi. Somehow, this sixteen year old boy is able to keep himself alive and coexist with a 450 lb tiger for months and months on a 25 foot boat. The tiger provides the impetus for Pi to stay alive and to gather enough food and water to keep both of them alive. Without the tiger, Pi wouldn't have survived the ordeal, yet Richard Parker is a constant threat to Pi's very existence. Together, they witness unimaginable beauty and almost unbelievable wonders.

But that's not what the book is about.

As a boy, Pi (his real name is Piscene Patel, but he chose Pi as a nickname to avoid the humiliation of other children calling him "Pissing" Patel) is fascinated by religion. Raised a Hindu, he is soon captivated by the beauty and depth of both Christianity and Islam. In one scene, Pi's parents are confronted in their home by three wise men, a priest, an imam, and a pandit, all of whom demand to know why they are each equally convinced that Pi is their most devout student. Pi honestly sees the beauty and the Truth in all of these religions and embraces each of them equally. He revels in their story telling and their rich histories. He finds significance in his everyday life through relating everything back to some Hindu scripture, or some Muslim prayer, or some New Testament parable. Pi is much more concerned with the act of having faith than he is in the truth behind each Faith.

Now this... this might be what the book is about.

"Life of Pi" is beautifully written and wonderfully descriptive (sometimes quite graphic when the tiger is devouring some unfortunate animal or when Pi is gutting a turtle). The adventure on the high seas is addictive. Once you started on that part of the book, you really couldn't put it down. But it became very obvious by the end of the novel, that the story meant something else. Yann Martel was trying to reveal some deeper truth to you through the gift of allegory. But the great thing about story telling, about allegory, about books in general, is that it doesn't really matter what the author or story teller is trying to say. A book doesn't belong to the author. It belongs to the reader. So, whatever lessons Martel intended to teach you might be lost on you, other readers may glean deeper truths from it, and learn more profound messages, but that doesn't mean that the book didn't teach you anything at all.

This book is about stories. It explores why we tell one another stories as part of our interaction, why we tell ourselves stories as well. They are not needed. Life will continue without our telling one another new (and old) stories over and over again. Stories make life worth living, and sometimes the stories we craft in our own heads, the narrative constructs that we fabricate to justify our actions even to ourselves, are the only things that keep us going.

"Life of Pi" is also, undoubtedly, about faith. It is a book that openly explores the idea of God and approaches him from many angles, including atheism. In fact, Martel heaps the most scorn on agnostics. "Doubt is useful for a while," Pi tells us early on in the book. "If Christ played with doubt, so must we... surely we are permitted to doubt. But," he warns, "We must move on. To choose doubt as a philosophy of life is akin to choosing immobility as a means of transportation." And later, in a paragraph that constitutes an entire chapter Pi tells us,

"I can imagine an atheist's last words: "White, white! L-L-Love! My God!" -- and the deathbed leap of faith. Whereas the agnostic, if he stays true to his reasonable self, if he stays beholden to dry, yeastless factuality, might try to explain the warm light bathing him by saying, "Possibly a f-f-failing oxygenation of the b-b-brain." and, to the very end, lack imagination and miss the better story."This is important because the story that unfolds after this is patently unbelievable. As wondrous as the story of the boy and the tiger on the boat is, as beautifully as it is told... it is unbelievable. But so what? Any good story deserves embellishment. Hell, you can't even talk about going to the grocery store without tossing in a few extra details! It doesn't matter anyway. There is power in truth, but what this book reminded you of is that there is more power in belief.

Truth simply explains. Faith inspires.

At the very end, in the last pages of the story, Pi tells a second, alternative story of his voyage. One that isn't as wonderful or beautiful, but is more believable. He challenges you to choose which story you prefer. There must be people out there who choose the second, more depressing, less fantastic story to put their faith in. But not you.

You will take the boy and the tiger every time.

You never want to miss the better story.

On to the next book!

No comments:

Post a Comment